Introduction to Graphs and Graph Modeling¶

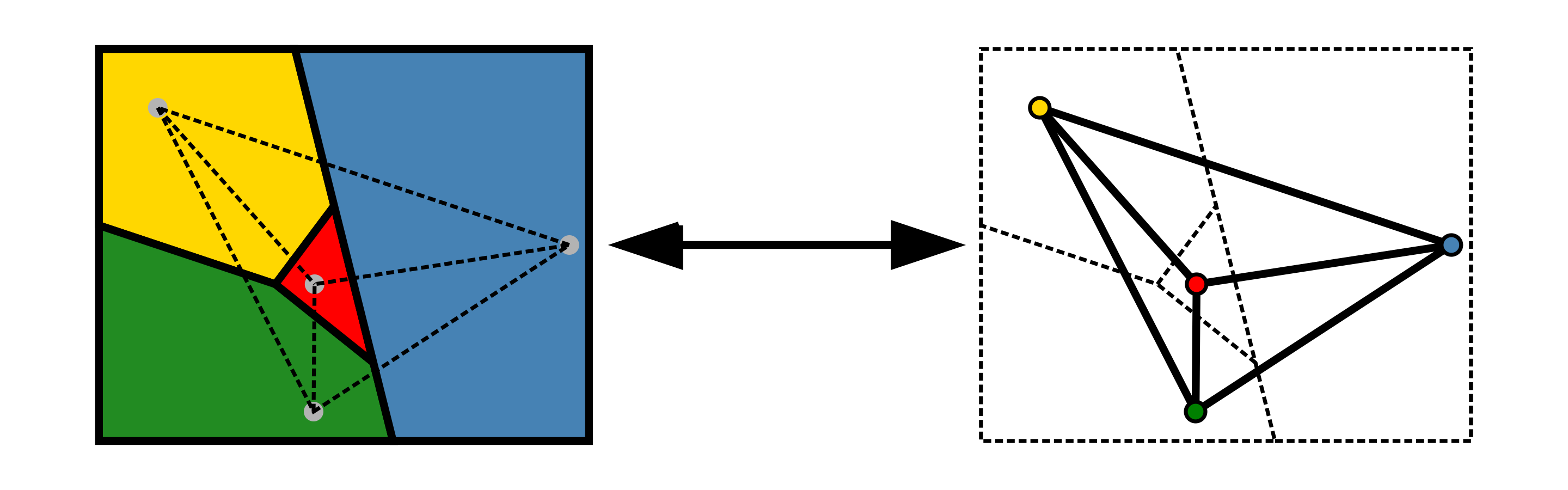

What is a graph? A graph is a set of points (entities) and lines (relationships). You can see a graph in Figure 1:

Figure 1¶

We call the points vertices and the lines edges. Each point and each line can represent something.

Why Graphs?¶

A graph is an abstract definition, like the number 2. In reality, there's no such thing as "2" itself, but there are, for example, 2 balls or 2 apples. Balls and apples are complex entities, and in problems (e.g., "how many balls are 2 balls plus 3 balls?"), this complexity doesn't matter. So, we eliminate these irrelevant details and focus on the important parts of the problem.

Suppose we want to travel between two cities, and there are roads connecting some cities in our country. Each road has a length and is either paved or unpaved, and we want to reach our destination from the origin in the shortest possible time. An active mind easily recognizes that in this problem, it doesn't matter whether we're traveling from one city to another, one country to another, or one village to another. So, it models the problem with an abstract definition like a graph. Cities become vertices, and roads become edges. For each edge, we know whether it's paved or unpaved and its length. With a little more thought, one realizes that being paved and the road's length are not important in themselves; they only affect the time it takes to travel a road. So, this is also removed, ultimately leading to a graph where each edge has a time value written on it.

Besides simplifying problems, abstraction helps us apply our solution from one problem to other problems. For example, once we understand that 2+3=5, it's easy for us to understand that 2 apples plus 3 apples equals 5 apples, or 2 pears plus 3 pears equals 5 pears. Or, in the cities example, if we can solve the problem for the abstract model "a graph with a time value written on each of its edges," we can use the same solution for routing packets in a computer network like the internet. Whereas, if we looked at the problem without an abstract approach, we might come up with a specialized solution (e.g., "if the road is paved, take the paved road, otherwise take the unpaved road"). This illustrates the benefit of abstraction and graphs as an abstract definition.

Where Do Graphs Appear?¶

Simple examples that come to mind are a set of people as vertices with friendship relationships between them as edges, cities and the roads between them, or the computer networks discussed above. But in fact, anywhere we deal with a relationship, graphs appear. For example, a family tree is a graph where each person has an edge to their parents. A more complex example, whose graph nature isn't immediately obvious, is a map. Each region on a map can be considered a vertex, and any two regions sharing a common border can be connected by an edge, thereby creating a graph:

A more complex example could be a game. For instance, we might want to model the entire game of chess as a graph. Each possible state of chess is considered a vertex, and an edge is placed between any two states if one can be transformed into the other by a single move of the player whose turn it is. This modeling covers a wide range of so-called board games. Some artificial intelligence algorithms for games use this abstract definition, which is why one algorithm can be used across many different games.

Simple Definitions¶

Definitions help us express our intentions more clearly, precisely, and with fewer words. There's no need to memorize the definitions. You will gradually learn these definitions by solving the exercises in this book. If you forget a definition at first, you can return here to see the meaning of the forgotten term. Also, all definitions in this book are summarized on this page.

Vertex and Edge: As mentioned above. These refer to the points and lines in a graph.

Loop: If a vertex has an edge to itself, that edge is called a loop.

Multiple Edges: If there are several edges between two vertices, those edges are called multiple edges.

Simple Graph: A graph that has no loops or multiple edges is a simple graph. We usually deal with simple graphs, so don't worry about loops and multiple edges.

Degree of a Vertex: The number of edges incident to a vertex is called its degree. For certain reasons, a loop is counted twice in the degree. If we denote the vertex itself by \(v\), we denote its degree by \(d_v\).

Minimum Degree of a Graph: The minimum degree of a graph is denoted by the lowercase Greek letter delta. If only one graph is under discussion, we simply use \(\delta\), and if several graphs like G and H are under discussion, we use \(\delta (G)\) and \(\delta (H)\).

Maximum Degree of a Graph: The maximum degree of a graph is denoted by the uppercase Greek letter delta. If only one graph is under discussion, we simply use \(\Delta\), and if several graphs like G and H are under discussion, we use \(\Delta (G)\) and \(\Delta (H)\).

Complement of a Simple Graph: The complement of a graph refers to a graph whose vertices are the same as the original graph's vertices, but an edge exists between any two vertices if and only if there is no edge between them in the original graph. By definition, the complement of a complement of a graph is the graph itself. The complement of graph G is denoted by \(\overline{G}\). In the figure below, the two four-vertex graphs, red and blue, are complements of each other:

Sum of All Degrees¶

In this section, we will prove a simple graph theorem together. It's a good idea to think about the solution a bit before reading the answer. The theorem states that the sum of the degrees of all vertices in a graph is twice the number of its edges, or in other words, \(\sum d_v = 2e\).

To prove this theorem, we examine the effect of each edge on the sum of the degrees of all vertices. An ordinary edge increases the degree of its two endpoints by one unit each, and a loop increases the degree of its single vertex by two units. Therefore, each edge adds exactly two units to the sum of degrees, so the sum of degrees is twice the number of edges.