Here's the English translation of the provided reStructuredText content:

Applications¶

Directed and Bipartite Graphs¶

In this section, we will see that the two concepts of bipartite and directed graphs are interconvertible, and depending on which one provides better intuition for solving a problem, we can use either of them.

Consider the adjacency matrix of a bipartite graph and a directed graph. Both are \(n*n\) matrices with entries 0 or 1. (Not necessarily symmetric)

Now, to convert a directed graph to a bipartite graph, it suffices to consider the adjacency matrix of the directed graph, which we call \(M\), and draw a bipartite graph whose adjacency matrix is \(M\). The conversion of a bipartite graph to a directed graph is similar. To look at it more intuitively, each edge \(ab\) in a directed graph is equivalent to an edge between vertex \(a\) from the left partition and vertex \(b\) from the right partition. That is, the left partition represents the outputs and the right partition represents the inputs.

Now consider a matching in a bipartite graph. If we convert the bipartite graph to a directed graph, what will our matching transform into?

A number of directed cycles and paths! This is because in a bipartite graph, at most one incident edge is chosen for each vertex, which in a directed graph means that each vertex has at most one in-degree and at most one out-degree.

Partitioning a DAG into Paths¶

We have a directed acyclic graph (DAG). What is the minimum \(x\) such that this graph can be partitioned into \(x\) directed paths?

Note that if in this optimal partition the number of edges in the paths is \(y\), then \(x+y=n\). So, to minimize \(x\), it suffices to maximize \(y\). Convert the directed graph to a bipartite graph. Now, \(y\) is equal to the maximum matching of this bipartite graph. (Why?)

Partitioning a Directed Graph into Cycles¶

Suppose we want to find a method to partition a directed graph into cycles.

First, convert the graph into bipartite form. We said that a matching signifies a partition into cycles and paths. You can easily conclude that a perfect matching provides us with a partition into cycles. So, it suffices to find a perfect matching in the bipartite graph.

2k-Regular Graph and Partitioning into Cycles¶

This time, our topic is an undirected graph. Similar to the problem above, imagine we have an undirected graph like \(G\) and we know it is \(2k\)-regular. We want to prove that there is a method to partition this graph into cycles.

The first idea is to replace each edge \(ab\) in \(G\) with two directed edges \(ab\) and \(ba\) in a directed graph. Then, similar to the problem above, first convert the directed graph into bipartite form and then try to find a perfect matching.

The problem that arises with this approach is that this partition might result in cycles of length 2 (which are essentially single edges), which is not desirable for us.

To prevent this problem, consider an Eulerian tour of the graph and direct each edge in the direction the Eulerian tour traverses it. (If the graph has multiple connected components, we do this for each component). Now, the resulting graph is a directed graph where each vertex has an in-degree and out-degree equal to \(k\). If we now convert this graph into bipartite form, each vertex will have degree \(k\).

According to a theorem we previously proved, a \(k\)-regular bipartite graph has a perfect matching, so there is also a method to partition this directed graph into cycles.

Degree Sequence of a Tournament and Matching¶

Suppose the sequence \(d_1,d_2,...d_n\) is given, and we know \(\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n} d_i = {n \choose 2}\). We want to check if there exists a tournament where the out-degree of each vertex \(u\) is equal to \(d_u\)?

Construct a bipartite graph. The right partition has \(n\) vertices, and the left partition has \(n \choose 2\) vertices, where each vertex in the left partition represents an edge of the tournament. Connect the vertex representing edge \(ab\) to vertex \(a\) and vertex \(b\) from the right partition. Now, choose a subset of edges such that the degree of each vertex in the left partition is 1, and the degree of vertex \(u\) in the right partition is \(d_u\). (Similar to a matching we discussed in the generalization of Hall's theorem section).

Intuitively, each vertex in the left partition, like the one representing \(ab\), must choose one of the two vertices \(a\) or \(b\). If it chooses \(a\), it means that in the tournament, the edge between \(a\) and \(b\) will be directed from \(a\) to \(b\), and vice versa. Also, the out-degree of vertex \(u\) in the tournament should be \(d_u\), so each vertex \(u\) from the right partition must be chosen by exactly \(d_u\) vertices from the left partition!

So, according to the topics we discussed in the generalization of Hall's theorem section, the necessary and sufficient condition for such a tournament to exist is that for every subset of vertices in the left partition, say \(S\), if the union of its neighbors in the right partition is \(P\), then: \(|S| \leq \sum\limits_{u \in P} d_u\) Since we can increase the left side to \(|P| \choose 2\) without changing the right side of the inequality (Why?), we can also write the condition as:

\(\forall_{P \subseteq \{1,2,...,n\}} {|P| \choose 2} \leq \sum\limits_{u \in P} d_u\)

Now, since only the number of elements in the set matters on the left side of the inequality, not the set itself, it is sufficient to check the condition for the smallest \(d_u\) values. In other words, assuming \(d_1 \leq d_2 \leq ... d_n\), the following condition is necessary and sufficient:

\(\forall_{1 \leq k \leq n} {k \choose 2} \leq \sum\limits_{i=1}^{k} d_i\)

Fixed Vertices in Bipartite Matching¶

We have a bipartite graph. For a matching \(M\), any vertex \(u\) incident to one of the edges in \(M\) is said to be covered by \(M\). Now, for all vertices \(u\), you need to determine if there exists a maximum matching such that \(u\) is not covered by this matching?

First, consider an arbitrary maximum matching, say \(M\). Now, for all vertices not covered by \(M\), we know the answer. We want to find the answer for each vertex \(u\) covered by \(M\). Suppose there exists a maximum matching \(M^{\prime}\) such that \(u\) is not covered by it. Now, let the symmetric difference of \(M\) and \(M^{\prime}\) be \(H\). In this case, \(H\) must consist of a number of cycles and even paths, and \(u\) must be an endpoint of one of these even paths (Why?)!

Thus, we conclude that for any vertex \(u\) that is covered by matching \(M\), we can find a matching in which \(u\) is not covered if and only if there exists an alternating path from a free vertex (a vertex not covered by matching \(M\)) to \(u\). Note that since this alternating path is not an augmenting path, its two ends are in the same partition of our bipartite graph.

So far, we haven't used the bipartite nature of the graph (all the statements made hold for any graph). But now, to find a maximum matching and the vertices that are the start of an alternating path, we must use the bipartite nature of the graph.

First, find the maximum matching \(M\) using the algorithm we presented in Section 12.2.

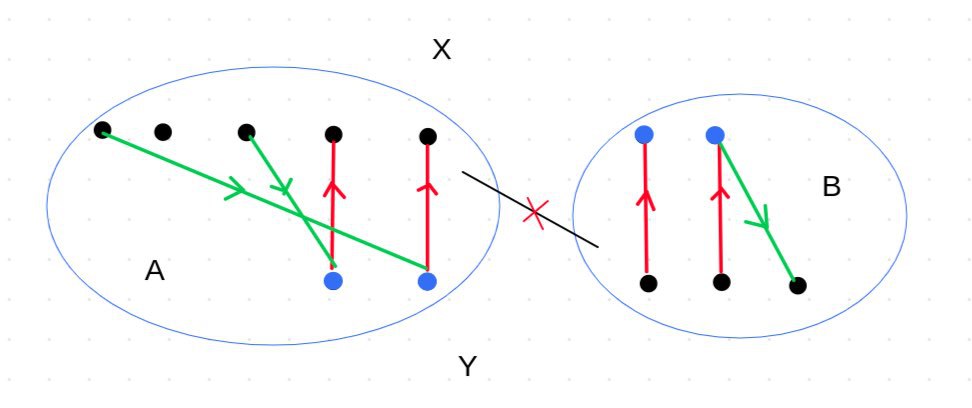

Now, suppose the two partitions of the graph are \(X\) and \(Y\), and we want to solve the problem for partition \(X\). We direct the edges of the graph such that edges belonging to \(M\) are directed from \(Y\) to \(X\), and edges not belonging to \(M\) are directed from \(X\) to \(Y\). You can see that any alternating path starting from a vertex in \(X\) is actually equivalent to a path in our directed graph that must start from one of the free vertices in \(X\).

So, it is enough to direct the graph as described, and then run a DFS algorithm from each free vertex in \(X\) to check which vertices are reachable. Ultimately, all vertices in \(X\) that we could reach are part of an alternating path. As we said, this implies that for each of those vertices, there exists a maximum matching in which that vertex is not covered.

Similarly, we can solve the problem for partition \(Y\) as well.

Finding a Minimum Vertex Cover in a Bipartite Graph¶

In Section 12.3, we learned that in a bipartite graph, the size of a minimum vertex cover is equal to the size of a maximum matching. In this section, we learn how to find a minimum vertex cover given a maximum matching.

First, consider the edges of the maximum matching and call it \(M\). Since for each edge of the matching, one of its endpoints must be in the vertex cover, exactly one of its two endpoints must be in the minimum vertex cover (Why?). So, for each edge in \(M\), it suffices to decide whether to include the vertex from the first partition or the vertex from the second partition in the vertex cover.

Name the two partitions of the graph \(X\) and \(Y\). Call the set of edges from \(M\) for which we choose the vertex from partition \(X\) as \(MX\), and the set of edges from \(M\) for which we choose the vertex from partition \(Y\) as \(MY\). Now we want to determine \(MX\) and \(MY\).

Similar to the previous section, we direct the edges of the bipartite graph such that edges belonging to \(M\) are directed from partition \(Y\) to \(X\), and edges not belonging to \(M\) are directed from \(X\) to \(Y\). Now, run DFS from all vertices in partition \(X\) that are not covered by the matching. Let \(A\) be all the reachable vertices, and \(B\) be the remaining ones. It is clear that there are no edges between \(X \cap A\) and \(Y \cap B\) (otherwise, the set \(A\) would change). Therefore, we can select all vertices in \(Y \cap A\) and \(X \cap B\) for the vertex cover. Since neither of these two sets contains free vertices (because \(M\) is maximum, so there are no augmenting paths), we can conclude that our statement is equivalent to assigning all edges seen in DFS to \(MY\) and the rest to \(MX\). That is, \(MX = M - MY\).