Proof of NP-Completeness of the SAT Problem¶

In the previous section, we became familiar with the definitions of NP-complete and NP-hard problems. You might think that it's impossible for an NP-complete problem to exist, but in this section, we will prove that the SAT problem is an NP-complete problem. This proof paves the way for proving the NP-completeness and NP-hardness of other problems.

Definitions of Problems¶

In this section, we will look at a few problems from the SAT problem family, which we will refer to later. The word SAT stands for satisfiability, meaning the ability to satisfy conditions. Each problem is a decision problem where we must provide an algorithm to check if the variables can be assigned values such that the overall expression/circuit evaluates to true (1).

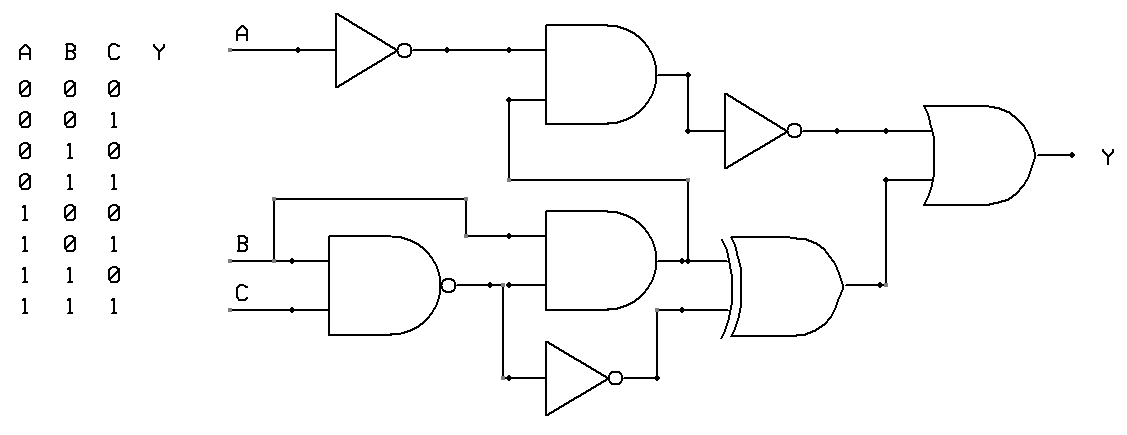

circuit-sat: In this problem, we are given a logical circuit composed of OR, AND, and NOT gates. This circuit has several inputs and exactly one output. The algorithm must determine if it's possible to set the inputs such that the output becomes one (true)? Note that the circuits taken as input for this problem are combinational logic circuits, meaning there are no cycles and the output of a gate does not affect its own inputs.

SAT: This problem is a special case of the above problem where the output is connected to a large AND gate, and each input of the AND gate is connected to a large OR gate, where each input of the OR gate is either connected to an input variable itself or to its negation. In other words, an expression in the form \((x_1 \lor x_7 \lor \overline{x_3}) \land ... \land (x_2 \lor \overline{x_1} \lor ... \lor x_7)\) is given to you, and you must determine if the variables can be replaced with 0s and 1s such that the result of the expression (the symbol similar to seven means logical OR, the symbol similar to eight means logical AND, and the line over a variable means logical NOT) becomes one (true).

3-SAT: This problem is a special case of the above problem where each clause (parenthesis) has exactly 3 variables. Similarly, 2-SAT is defined, whose solution algorithm you will learn in other chapters.

Proof of NP-Completeness of Circuit-SAT¶

Consider an arbitrary NP problem. This problem has a polynomial-time verifier. Each verifier is itself a decision problem. The key point is that any decision algorithm that has a polynomial running time can be converted into a combinational logic circuit. Although the precise proof of this requires a deeper understanding of algorithms and is not suitable for this book, you can try it on problems at hand. For example, provide a circuit for the verifier of the Hamiltonian cycle problem or the graph coloring problem.

Therefore, for an input of fixed length, we convert the decision algorithm into a combinational logic circuit whose number of gates is polynomial with respect to the input. Now, if the verifier can be given an input that it accepts, then its equivalent circuit can also be given an input such that its output becomes one (true). Thus, the answer to the original problem is equivalent to the result of Circuit-SAT on this circuit. Therefore, any problem in the NP class can be reduced to the Circuit-SAT problem in polynomial time, and thus Circuit-SAT is an NP-complete problem.

Reduction from Circuit-SAT to SAT¶

In this section, we will prove that the 3-SAT problem is also an NP-complete problem, and from that, it follows that the more general case, the SAT problem, is also NP-complete. First, note that the exact requirement of three variables per clause is not critical, as clauses can be enlarged by adding duplicate variables, for example, transforming \((x \lor \overline{y})\) into \((x \lor \overline{y} \lor \overline{y})\).

Now consider a combinational circuit. First, convert all AND or OR gates that have more than two inputs into two-input gates. This increases the input length linearly, which is not significant for us. Now, for each set of equipotential points (i.e., points connected by a wire), we introduce a variable. Then, for each gate, we add several conditions to ensure its behavior. That is, the conditions hold only if the gate's output corresponds to its inputs and its function. For example, suppose \(a\) and \(b\) are the inputs to an AND gate, and \(x\) is its output. By adding the clauses \(\overline{a} \lor \overline{b} \lor x\) and \(a \lor \overline{x}\) and \(b \lor \overline{x}\) we can ensure that the value of \(x\) is necessarily equal to the logical AND of \(a\) and \(b\). Similarly, such conditions can be defined for OR gates and NOT gates. By conjoining (ANDing) these conditions and the circuit's output variable itself, one can construct an input for 3-SAT such that its satisfiability is equivalent to the satisfiability of the same circuit in Circuit-SAT. Thus, this problem and its general form, SAT, are both NP-complete.